ARTICLES AND INSIGHTS

The Changing Topology of Tokyo’s Central Three Wards

How have Chiyoda, Chuo and Minato wards changed over the years?

Chiyoda, Chuo and Minato wards make up Tokyo’s “Central Three Wards”

Over the past few years, it has become clear that the shape and properties of the ground, in other words its topology, is closely related to natural disasters. By understanding the geography of an area, we can not only learn more about past disasters, but also predict the dangers posed by potential future disasters.

However, the topology we see today is not always the same as it was in the past. As you may know, when Ieyasu Tokugawa entered Tokyo, many of these areas were part of the sea. Edo was urbanized and expanded by reclaiming land and excavating waterways. Here we will look at the significant changes that took place in the area and how Tokyo’s central three wards, namely Chiyoda Ward, Chuo Ward, and Minato Ward, have changed in the intervening time.

Konjaku (“Now-and-Then”) Map on the Web is an effective website for learning about historical land utilization

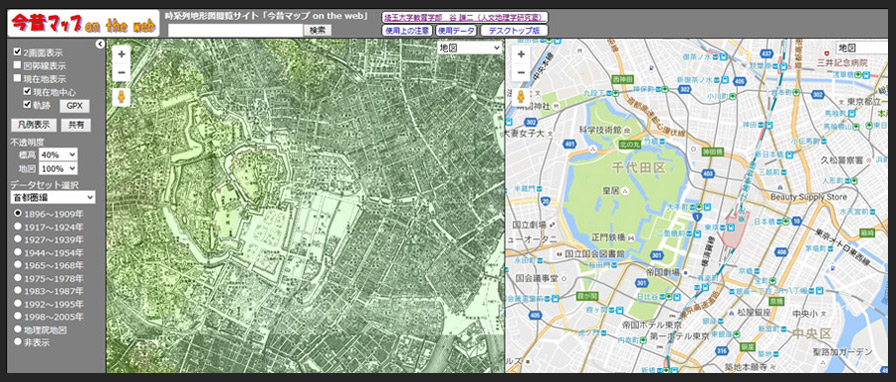

Konjaku Map on the Web: http://ktgis.net/kjmapw/ (click to enlarge)

This view is of the Tokyo metropolitan area. The maps on the left and right allow old and new maps to be compared at a glance. The current version of the website allows display of four versions of maps.

Let’s start with an introduction to a website that is useful for learning about how land utilization has changed. After the Great East Japan Earthquake, there were reports of a growing number of people visiting libraries and consulting old editions of maps to learn about the properties of the land in years past. Fortunately, this led to the appearance of an application that lets you to arrange old and current maps side-by-side to compare them at a glance. Konjaku Map on the Web is a web-based version of this chronological topographical map viewing application that was released in 2013.

Developed by associate professor Kenji Tani at the Faculty of Education of Saitama University, Konjaku Map allows users to switch between nine types of map covering the periods of 1896 through to 2005 in major cities from Sapporo to the north and the southern area of Okinawa’s main island to the south. As you adjust the view of an old map on the left, the position of the modern-day map on the right is synchronized, while the mouse cursor is also reproduced so that individual points can be identified across both views. To the uninitiated, old maps list place names that differ from their modern-day equivalents and may offer few clues when searching for locations such as specific train lines or roads, but this site eliminates that issue that allows you to easily discover the differences between past and present maps.

Land reclamation and former samurai residences sum up how Tokyo’s central three wards have changed

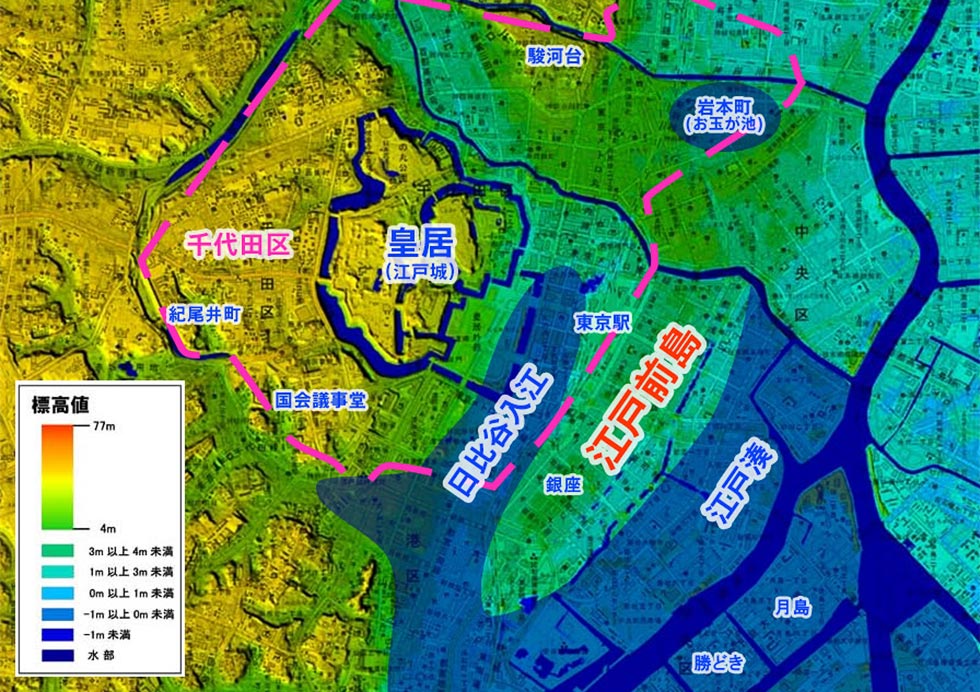

Digital topographical map of land elevation (1)

This is an edited map taken from the website of the Geospatial Information Authority of Japan , cut out from the section showing Tokyo’s wards, with the Ginza area as the center. This provides an overview of how the area was laid out during the Edo period in relation to familiar modern-day landmarks.

The key concept that describes how the topology of Tokyo’s central three wards has changed

is land reclamation. This has taken two forms, reclamation from the sea, and from river systems.

In terms of reclamation from the sea, around the time Ieyasu Tokugawa entered Edo, an

inlet known as the Hibiya Inlet extended to the front of Edo Castle, which stands at the eastern end of

the Musashino Plateau, and a peninsula known as Edomae Peninsula jutted out on the opposite side of the

inlet. This is also faintly visible in the present-day digital topographical map of land elevation (1)

(above). Immediately after entering Edo, the Tokugawa Shogunate levelled off Kanda Hill (the area today

known as Surugadai) and began transforming Edo by filling in the Hibiya Inlet. Land was steadily

reclaimed from the seaward side thereafter. The area around the Tokaido Road provides an extremely rough

estimate of the coastline during the Edo period. From the Meiji Period onwards, assiduous efforts to

reclaim land outward from this point have continued.

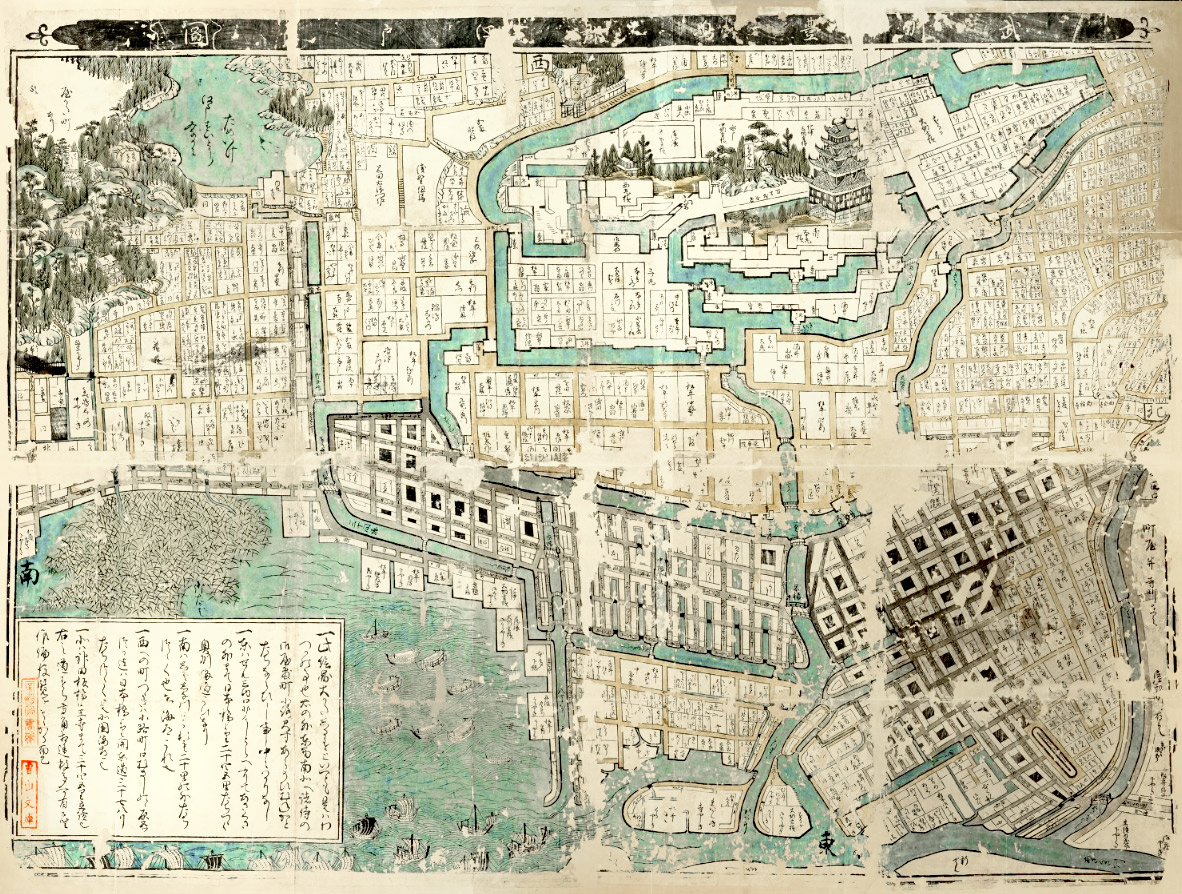

Bushu Toshima-gun Edo Shozu Map drawn up around the time of Iemitsu, the third Tokugawa Shogun (click to enlarge)

This map is regarded as the oldest existing map of Edo. From the website of the National Diet Library

Another form of land reclamation targeted rivers. A look at the Bushu Toshima-gun Edo Shozu map drawn up around the time of the third Tokugawa Shogun Iemitsu (left) depicts multiple waterways that do not exist today running through the city. Period novels depicting Tokyo during the Edo period describe a place much like the Italian city of Venice where water was a common means of transportation. However, many of these waterways were subsequently filled in. This occurred in two major stages, first in the aftermath of the Great Kanto Earthquake, and later during the Second World War, in both cases as a way to dispose of rubble and surplus soil. At some point other rivers of which there are no official records were also filled in, and the waterways of Edo gradually disappeared as the move away from water transportation progressed.

Tokyo Garden Terrace Kioicho

This complex was completed in 2016 on the former site of the Grand Prince Hotel Akasaka. Kioi-cho was once the location of compounds belonging to the Kii and Owari families, two of the three Tokugawa house branch families, as well as the Hikone Ii family.

While somewhat separate from the topology itself, changes to sites such as former daimyo

residences located in the heart of Tokyo also provide an interesting perspective on how the land has

changed over time. Daimyo residences in the city center were often situated at good elevated locations.

They later became the homes of Meiji Era statesmen, aristocrats and financiers, and are today dominated

by hotels, universities, government buildings and regular homes. If a plot of land is where one of these

residences once stood, it offers peace of mind in terms of both the subsoil and living environment.

Now let’s look at each of the three central wards of Tokyo in turn.

Chiyoda Ward

The ward was transformed mainly during the Edo Period with the filling in of the Hibiya Inlet and other changes. Boundaries between wards were always demarked by rivers.

From left: Kudanshita, Chidori-ga-fuchi and Kanda

The topology of Chiyoda Ward is broadly split into two sections, the boundary of which is the Imperial Palace (formerly Edo Castle). As the above digital topographical map of land elevation (1) shows, the area to the east of the Imperial Palace is low-lying land, while to the west is a plateau. On the low-lying land on the western side, the long and narrow Hongo Plateau where the University of Tokyo is located extends to the south, continuing on to what was once the Edomae Peninsula.

Since Chiyoda Ward has been a central area from the Edo Period onward, it has undergone continual transformation since the early days of Tokugawa’s arrival in Edo, and today’s Chiyoda Ward looks almost nothing like it did during the Edo Period. As detailed earlier, the filling in of the Hibiya Inlet (center area of the digital topographical map of land elevation (1)) was commenced immediately after Tokugawa’s arrival in Edo, and Otamagaike Pond (top right of the digital topographical map of land elevation (1)), which is believed to have extended from what is now Iwamotocho 2-Chome to Kajicho 2-Chome had been almost completely filled in by the year 1632.

Rivers in Chiyoda ward included Aizome River, which ran around Otamagaike Pond and flowed into the Kanda River, the Dosan Canal that ran from around the Wadakuramon Gate linking the outer and inner moats of Edo Castle, and the Uchiyamashita moat running from the enter of Hibiya Park and flowing into the Sotoborigawa River. These were filled in from the Meiji Era onwards, and in some locations today even the traces of waterways cannot be seen.

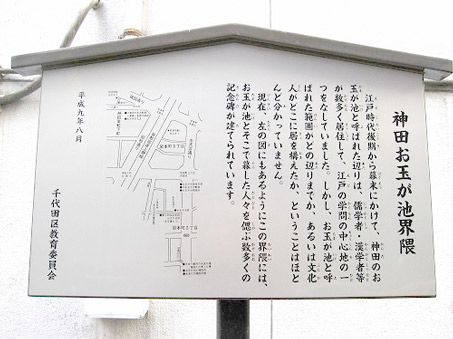

A description of Otamagaike Pond posted in Iwamoto-cho

Otamagaike Pond is believed to have been larger than Ueno’s Shinobazu Pond. From the Chiyoda City Tourism Association blog.

Area between Kanda in Chiyoda Ward and Nihombashi in Chuo Ward: Comparison of 1927-1939 and Today (From Konjaku Map on the Web )

The flow path of the Ryukan River highlighted in blue. The river can be identified from the bridge symbols inscribed on the map.

The boundary between Chiyoda Ward and other wards reveal definitive traces of former rivers. Like the Kanda River as the boundary with Bunkyo Ward and the outer moat forming the boundary with Shinjuku Ward, rivers demark the boundaries between Chiyoda Ward and other wards. Among them, many have become closed culverts in the present day. For instance, the Ryukan River formed a section running from Kanda in Chiyoda Ward to Nihombashi in Chuo Ward. The river was filled in in 1950 and formed into a main sewage duct. The area highlighted in blue on the above map from 1927 to 1939 depicts the position of the Ryukan River, with the present-day map from Konjaku Map on the Web shown alongside. Along Sotobori-Dori Street is the Ryukan-Bashi Intersection, and it was from around this point that the river ran along the present-day ward boundary, eventually feeding into the Hamacho River, which also does not exist today. While Imagawabashi Intersection remains in the area, it was originally the name of the bridge which once spanned the river.

Meanwhile, the Sotobori River demarked the boundary between Chiyoda Ward and the Nihombashi, Yaesu and Ginza areas of Chuo Ward. The many intersection names ending with hashi/bashi ("bridge") from Gofukubashi to Dobashi offer convincing evidence that the section was once a river. In Chiyoda Ward and other locations throughout the city center, a great many places and intersections include hashi/bashi in their names, in each case indicating that there was once a bridge spanning a river at that point.

Traces of the Sotobori River (edited Google Maps view)

From Gofukubashi to Dobashi, many of the place names end with "hashi/bashi", meaning "bridge".

Chuo Ward

There were many canals in Nihombashi and Kyobashi. The ward’s coastal sections have expanded with the times to take their present form.

From left: Nihombashi, Kachidoki and Harumi

Of Tokyo’s central three wards, Chuo Ward is the flattest with the fewest slopes. This is because a lot of Chuo Ward is made up of the flat peninsula known as Edomae Peninsula along with land that was reclaimed from the Edo Period onwards. The section from Ginza to Shimbashi has the highest elevation in the ward, standing at 4m above sea level. The high points of other wards, including 30m in Rokubancho in Chiyoda Ward and 26m at Atagoyama, Minato Ward show just how low-lying the Chuo Ward is by comparison.

Even so, we should be careful not to conflate low with dangerous. In 1934, geological surveys were conducted in the Ginza area located at the tip of what was the Edomae Peninsula as part of work to construct the Tokyo Metro Ginza Line, and the results indicated stable subsoil composed of sandbar deposits. Incidentally, Ginza was once completely enclosed by rivers. This is easy to envisage by looking at Shimbashi and Kyobashi at either end of Ginza-dori Avenue, and the points from Sukiyabashi to Mannenbashi on Harumi-dori Street running north to south. In total there were 25 bridges surrounding this area and six interior bridges spanning east to west, suggesting just how much the area has changed.

Shuto Expressway near the Shintomi-cho Exit (click to enlarge)

Top: From Google Earth / Bottom: From GoogleStreet View

As the Nihombashi and Kyobashi areas inside Chuo Ward were hubs of Edo that functioned as ports, for water transportation, many now-defunct rivers connected to them, including the Kyobashi River, Sakura River, Tsukiji River, Shiodome River, Sanjikken-bori River, Teppozu River, Hakozaki River and Hamacho River. Today, however, few of these rivers remain, such as the Nihombashi River and Kamejima River. Most rivers have changed into roads including Shuto Expressway.

Starting in 1960 the rivers were filled in over several stages, including the parts intersecting with the section of the Shuto Expressway running between Nihombashihoncho and Shiodome which entered service in 1962 as Route 1. In particular, the 1.2 kilometer section of the Tsukiji River running from Ginza to Shintomicho was drained and a road was constructed along the riverbed, with the semi-underground canal structure creating a section of successive sharp curves. Since more than half a century has passed since it entered service, upgrades are currently being considered, and eventually the signs revealing the fact that it was a river may disappear. In addition to the road, Tsukijigawa Park also preserves the name of the river.

Changes to Tsukudajima, Tsukishima and Kachidoki (from Konjaku Map on the Web )

When maps from 1896-1909, 1927-1939 and 2016 are arranged side-by-side, we can see how land reclamation has progressed with time. Firstly, as of 1896-1909, the only areas of reclaimed land were Tsukudajima, Tsukishima and Kachidoki, which were formed using earth from dredging operations undertaken to preserve the water depth in Tokyo Bay from the end of the Edo Period to the early Meiji Period.

Then, over a period of around three decades, the islands of Harumi and Toyosu were constructed by landfill. After World War II, the Kachidoki 5-Chome and 6-Chome sections and up to around half of the Harumi 5-Chome section were constructed. During Japan’s high economic growth period Harumi Wharf was also created through land reclamation, completing what is Chuo Ward’s current form.

Minato Ward

Minato Ward features low-lying areas along both banks of the Furukawa River, a plateau that extends north to south, and many springs

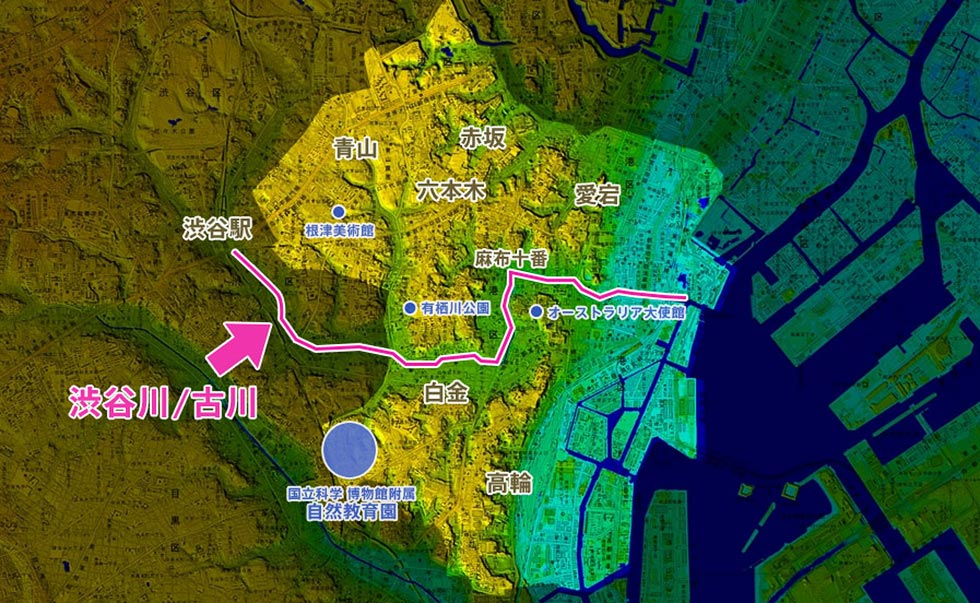

Geospatial Information Authority of Japan Digital topographical map of land elevation (2)

This is an edited map taken from the website of the Geospatial Information Authority of Japan , with Minato Ward cut out from the section showing Tokyo’s wards.

Like Chiyoda Ward, Minato Ward is divided into two main areas, a low-lying area and a plateau, and also features many hills. Almost 90 such hills are highlighted on the website of Minato Ward, and as many are named after daimyo residences or the people who once lived there, they offer insight into the history of the town. Another feature is the large number of springs located in the area between the plateau and low-lying areas. Noted spots include the marsh of the Institute of Nature Study which still retains the atmosphere of Musashino, Hyotan Pond, and the ponds at Arisugawa-no-miya Memorial Park and the Nezu Museum. These locations make use of springs from a plateau known as the Yodobashi Plateau. Despite its location in the city center, Minato Ward retains a surprising amount of nature.

While the topology of Chiyoda Ward is separated into two by the Imperial Palace, in the case of Minato Ward it is the Furukawa River. The river is a downstream extension of the Shibuyagawa River, and today both rivers have very little flow and are lined with concrete revetments. For this reason, its force as a river tends to be dismissed, but the low-lying areas of Minato Ward that extend out from both banks underscore the significant role the river played in shaping the surrounding topology. One of the most well-known low-lying areas along the Furukawa River is the Azabu-Juban neighborhood (located in the center of the Geospatial Information Authority of Japan Digital topographical map of land elevation (2)). During the Edo Period, these low-lying areas contained a large number of stores and the homes of commoners. The concentration of long-established stores in Azabu-Juban and the ordinary downtown atmosphere that is preserved is largely due to this history.

Meanwhile, plateaus around the Furukawa River include Azabu, Iikura, Aoyama and Akasaka to the north, while to the south, Shirokane, Takanawa and Mita feature terraces. If you look in the direction of Azabu-Juban from the vicinity of the Australian Embassy in Mita, you will be able to appreciate the large difference in elevation.

As with other wards, various rivers have been filled in around Minato Ward, but in connection with this, one location that has changed significantly from the past is Tameike, which means “reservoir” in Japanese. Today, the only vestiges that remain are in the names of intersections and train stations, but long ago, the original form of the reservoir was fed by water flowing out from around Sugacho in Shinjuku Ward which flowed through the Edo residence of the Kishu Tokugawa clan (now the site of the State Guesthouse and Akasaka Palace) and was connected from the moat at Akasaka-Mitsuke to Toranomon. According to Edo Period literature, it was an extremely large pond. However, filling in of the pond began from around 1650, and it had all but disappeared by the middle of the Meiji Era. The Shiodome River running along the border of Chiyoda and Chuo wards was created as a drainage canal for this pond and the outer moat, and was also filled in following World War II. Several other rivers including the Akasaka River, Sakura River and Uda River ran between the Shiodome and Furukawa rivers, but these were also filled in following the Great Kanto Earthquake.

Coastal land reclamation was focused around the Konan area from Hamarikyu to Shinagawa. The Tokaido Road once ran along the coast, and even Meiji-era maps depict the Tokaido route closely tracking the coast. The ruins of the Takanawa Okido Gate situated north-east of the Sengakuji Intersection on the Daiichi-Keihin Road show what the area was like clearly. This was the entrance to Edo, serving as a point marking the city limits while also separating land from sea. If you stand at the spot with this in mind, you will be able appreciate the magnitude of changes that have occurred in Tokyo.

An illustrated guide to the hills of Minato Ward

From the Minato City website

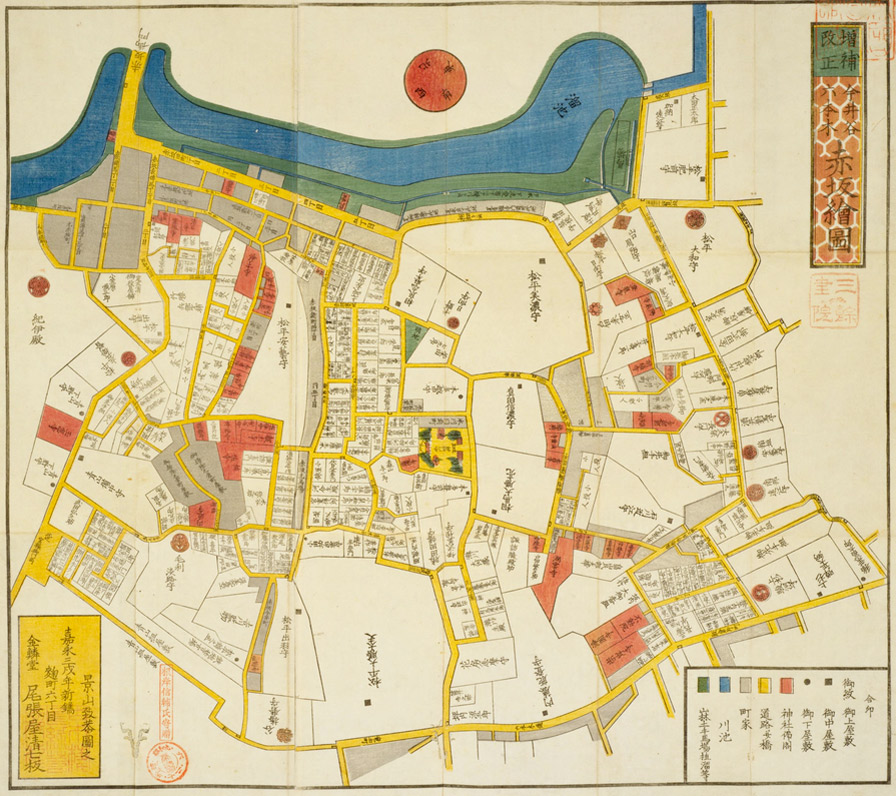

[Detailed “Kirie-zu” Maps of Edo: Map of Akasaka] From the Website of the National Diet Library .

From the Akasaka section of the detailed Kirie-zu maps of Edo printed between 1849 and 1862, we can see that a riding ground had been created in the vicinity of the pond, and that the filling in of the pond had already progressed.

Akasaka-Mitsuke

Area between Shinagawa Station and Tamachi Station: Comparison between 1896-1909 and Today (from Konjaku Map on the Web )

Between the characters “動” and “本” of “海道本線” on the map on the side of the land, the characters ”大木戸” (Okido Gate) can be seen. This was the entrance to Edo. The names of two residences inland of Shinagawa Station are also visible.

Like the city center, the Shinagawa neighborhood also contained many official residences. The Kitashirakawa Residence and Takeda Residence can be seen on the above map, and the Mori House is also close by. Each of these sites are now the locations of Prince Hotels. With its elevated position despite the proximity to the sea, it is believed this was once a favorable location offering views of Tokyo Bay.

This completes our brief look at the changes that have taken place in Tokyo’s central three wards. Since all three wards have long histories, there are still many changes not touched upon in this article. Not only in terms of disaster prevention but to develop an affection for the area, we encourage you to learn about the history of where you live or hope to live.

• The maps used in this article were created using the Konjaku Map on the Web chronological topographical map viewing website. (© Kenji Tani).

* This is a translation of a Japanese article.

* The information in this article is current as of May 2016.

Hiroko Nakagawa

For more than two decades, Nakagawa has been involved in editing magazines, books and websites on

living-related issues such as purchasing, leasing and building. Nakagawa has lived in Omotesando for many years,

and is keenly aware of the comfort of living in central Tokyo.

Nakagawa is the author of an All About

Guidebook titled Sumiyasui Machierabi: Shutoken (Finding a livable town: Tokyo metropolitan area).